28 nov. 2025

Breuer et al. (BioRxiv) DOI: 10.1101/2025.09.18.677123

Keywords

Tumor-draining lymph nodes

Metastasis

Immune checkpoint blockade

Main Findings

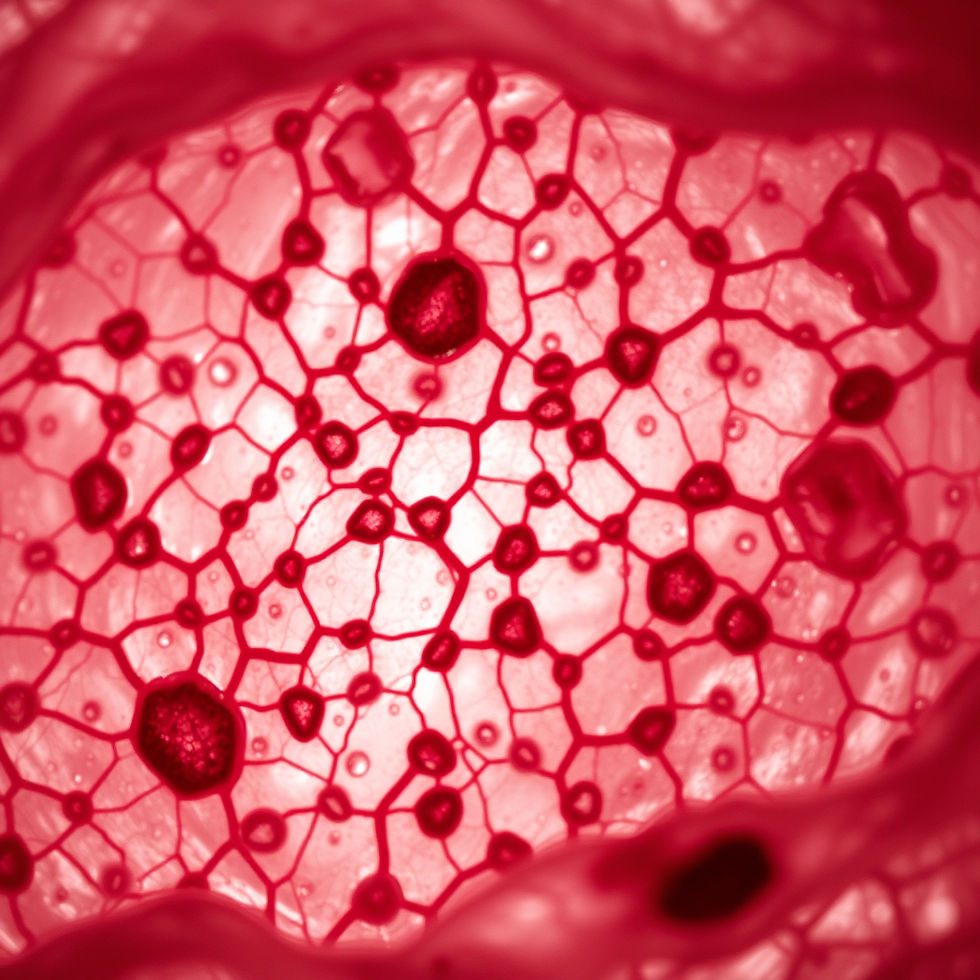

Lymph nodes are the central hub for the initiation of immune responses. However, their role in driving anti-tumor responses is still not fully understood. Especially during metastasis formation, the function of the tumor-draining lymph nodes is often disputed in whether they are beneficial or detrimental to tumor dissemination and therapy response. In this preprint, Breuer et al aim to investigate the tumor-intrinsic determinants of lymph node and distant-organ metastasis and how the potential to seed specific sites impacts the response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy (ICB). They primarily utilize the B16/LN8 melanoma model to study metastatic dissemination to the lymph nodes and peripheral organs, in vivo clonotype tracking models, as well as data from patients with metastatic disease to show that tumor cells differentially sense type I interferon (IFN), which in turn determines the type of metastasis (lymph node vs. peripheral) and therapy response to ICB. This preprint specifically highlights that:

Lymphocytes in lymph-node metastatic cancers are producers of type I IFN.

Primary tumor clones express different interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) signatures and ISGhigh clones are more likely to seed the lymph nodes while ISGlow clones seed peripheral organs.

Treating mice with IFNa sensitizes ICB-refractory distant metastases to ICB.

While the authors convincingly show that type I IFN plays a deterministic role in metastasis formation, some additional experiments could help strengthen some of their claims (see below).

Limitations

The authors claim that the majority of type I IFN is produced by lymphocytes and want to validate this by flow cytometry. In their methods, a 12-hour stimulation with PMA/Ionomycin and Brefeldin A is said to be used to detect IFNa. This seems like an excessively long time and cell viability should be carefully assessed after this amount of time with Brefeldin A. On the histograms shown, positive populations are sometimes hard to distinguish and it is unclear whether the whole population is shown or whether it was already pre-gated. It would be helpful to include the actual gates in the figures that reflect the quantified data in Figure 1 (e.g. in figure 1S approximately 10-20% of NK cells are quantified as IFNa+ but on the histogram it looks to be much more). Additionally, the authors should include FMO stainings for these histograms to assess the positive populations more clearly. In general, it might be more informative to perform an ELISA from the supernatant of these stimulated cells to quantify IFNa production rather than flow cytometry, which is known to be difficult for these cytokines.

The mechanistic details of this paper remain a bit elusive. The authors could investigate, for example, what drives lymphocytes in LN-trophic tumors to produce more IFNa. The question of cause and effect arises here – do lymphocytes produce IFNa which in turn drives LN metastasis (if yes, why is this enhanced in the LN8 model?) or do some tumor cells produce IFNa which leads to tumor cells becoming more LN-metastatic and drive T cells to produce more IFNa? This could be at least partially disentangled by using and IFNAR knockout in T cells/lymphocytes to dissect the contribution of these cells to LN metastasis.

Immunogenicity of the different tumor models is briefly mentioned as an explanation for the different metastatic profiles. However, only PD-L1 and MHC-I are assed in this. The fact that NK cells kill more in the absence of MHC is their main mechanism of cancer detection and hence not surprising. Again, it would be interesting to know what drives this phenotype on the cancer cells and how whether ISG expression is the cause or consequence of this phenomenon.

Alternatively, if the authors are not equipped to perform immunology-oriented mechanistic experiments, it would be important to more closely investigate the metastatic switch in their ISGhigh cells. Do these cells express specific chemokine receptors that makes them better at migrating to the LN compared to distant tissues? They already have scRNA-seq from their evolution experiment which could be utilized more deeply to show what drives this different tropism over the course of metastatic dissemination.

Overall, the question of why IFNAR signalling is so clearly important for LN adaptation in these clones is not answered. This goes along with the above-mentioned suggestions of investing more time to assess the changes within the tumor cells that drive these differential adaptations to the LN vs. the periphery.

Over the course of the paper, the authors convincingly show that IFNa treatment can determine the metastatic site of the primary tumor. They utilize this to show that IFNa treatment can also sensitize distant metastases to ICB. This also implicates that there could be more LN metastases in the groups treated with IFNa+ICB. Was this an observation the authors made in their mice? In any case, data for this should be shown and/or this possibility should be included in the discussion.

Significance/Novelty

This preprint adds to existing literature challenging the notion that LN metastasis is a first step in metastatic dissemination and convincingly show that exposure to IFNa can drive primary tumor clones to metastasize to the LN rather than peripheral tissue and vice versa. This has large implications for patients on two levels: whether to performing preventive lymphadenectomy is useful and potentially using IFNa to sensitize therapy-refractory patients to ICB. While the mechanistic insights into the processes described here need to be explored more, this data will have a direct impact on understanding metastatic dissemination and therapy response.

Credit

Reviewed by Teresa Neuwirth as part of a cross-institutional journal club between the Max-Delbrück Center Berlin, the Ragon Institute Boston (Mass General, MIT, Harvard), the University of Virginia, the Medical University of Vienna and other life science institutes in Vienna.

The author declares no conflict of interests in relation to their involvement in the review.